Foxconn Reconnecting With its Past is the Future America Needs

[Opinion] Taiwanese and American companies share a common future, US leaders need to recognize that fact.

Good Evening from Taipei,

Foxconn is a connector company. It’s right there in the name.

Chairman Liu Young-way took pains to remind guests of that fact at this year’s Hon Hai Technology Day. Although the Taiwanese company is famous for assembling final devices — such as iPhones, PlayStations and Kindles — end-product manufacturing is a relatively new business: commencing in the mid-1990s more than 20 years after Terry Gou founded Hon Hai Plastics.

This distinction matters. It matters for Foxconn. And it matters for America. Final-assembly of smart consumer devices like cellphones and games consoles is labor intensive, low-priced, low-margin, and high volume. That’s perfectly suited to a low-wage country with a large labor pool like China, where Foxconn has most of its factories. Not so much the US, which wants more factories.

High-value, high-margin, or highly automated manufacturing is a much better fit for America. So when Liu, who took over from Gou in 2019, reminded people of Foxconn’s roots at its annual confab last week it felt like he was talking directly to Americans. Hon Hai is the name Gou gave to the plastics-manufacturing company he founded with seed capital from his mother in 1974, but Foxconn is the Westernized moniker he bestowed upon the business when he started chasing more clients in the US. The conn comes from connectors.

Incidentally, Gou made a surprise return to HHTD this year. His mother passed away a few weeks ago. I don’t know if the two are related, but Liu made a point of offering his condolences on stage.

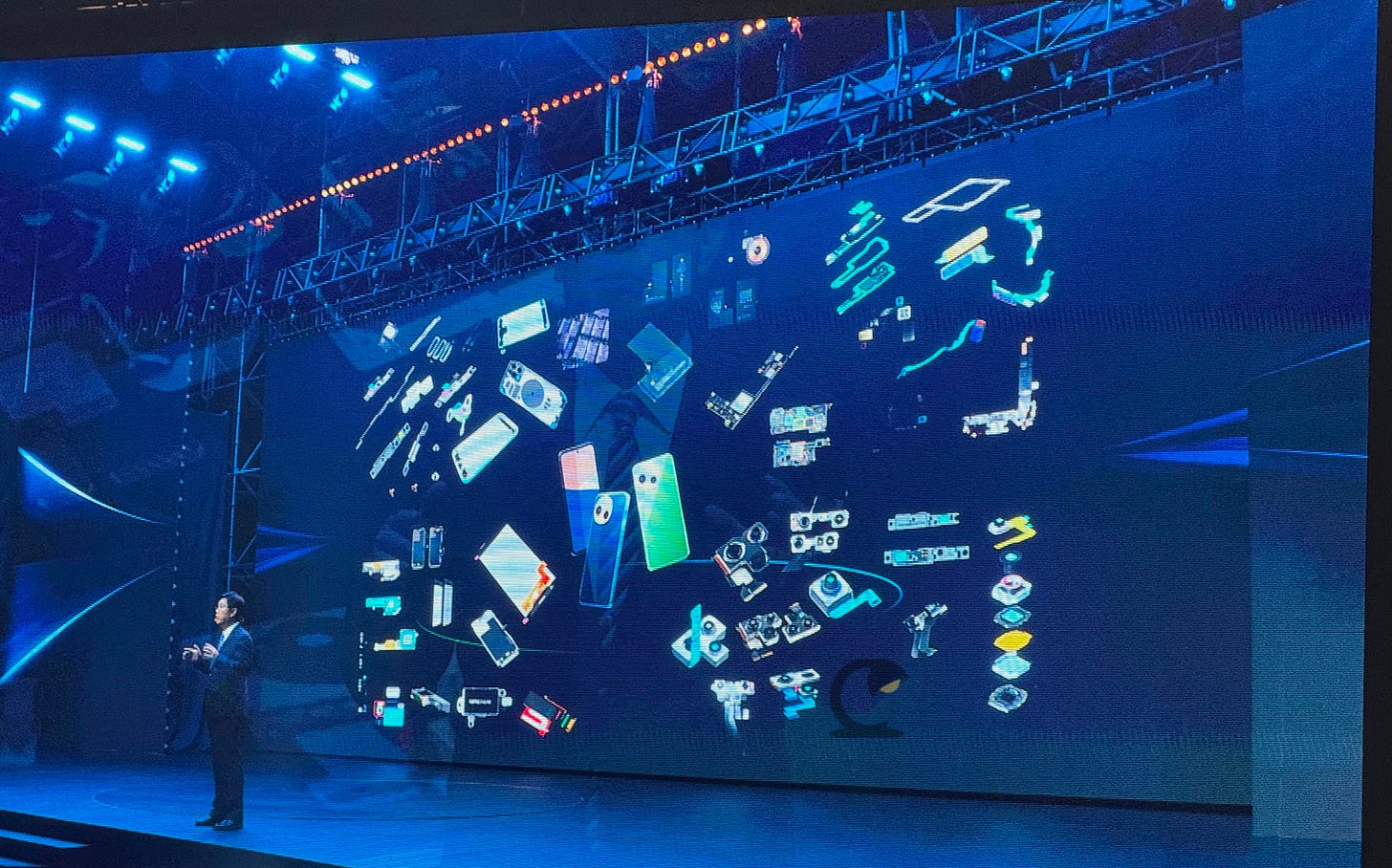

Showing off an array of components, cables, and connectors, Liu suggested people remember the term “Foxconn Inside.” Just 50 meters away, at its product showcase, Foxconn staff were on hand to introduce exactly the items he was talking about. Cooling pipes and heatsinks, power junctions, printed-circuit boards, and wafers of semiconductors — yes, Foxconn makes chips.

Last year I criticized Liu’s presentation for focusing too much on its production of finished cars, when instead I felt he could have spent more time explaining the heart of Foxconn’s business model, which is components.

“I think the company is at grave risk of screwing up if it keeps rolling out completed cars, as though it expects some incumbent or startup to just rebadge a Foxconn model with their own name. Its mixed messaging is painful to watch,” — Hon Hai Tech Day & the Future of the Global Economy.

I feel somewhat vindicated that he went back to the company’s origin story, and it turned out to be Liu’s best HHTD presentation to date. Talking about components, which may not be as sexy as iPhones, helps Foxconn explain itself to foreign leaders who seem obsessed with getting iPhone manufacturing to their shores.

During his first term, President Trump urged Apple to make its iPhones in the US. He continued that campaign in the lead up to his second term, culminating in CEO Tim Cook announcing $500 billion of investments into the US soon after Trump took office for his encore performance.

But Apple isn’t doing most of that work, Taiwanese companies like Foxconn and TSMC are. Foxconn’s disastrous adventure in Wisconsin rightly soured many Americans on the Taipei-based company, just a few years after it was pilloried for working conditions at its China factories.

Behind the scenes though, Foxconn has been expanding its operations across numerous US states, including a series of massive factories in northern Houston. They’re not making iPhones in the US. They likely never will. And that’s okay.

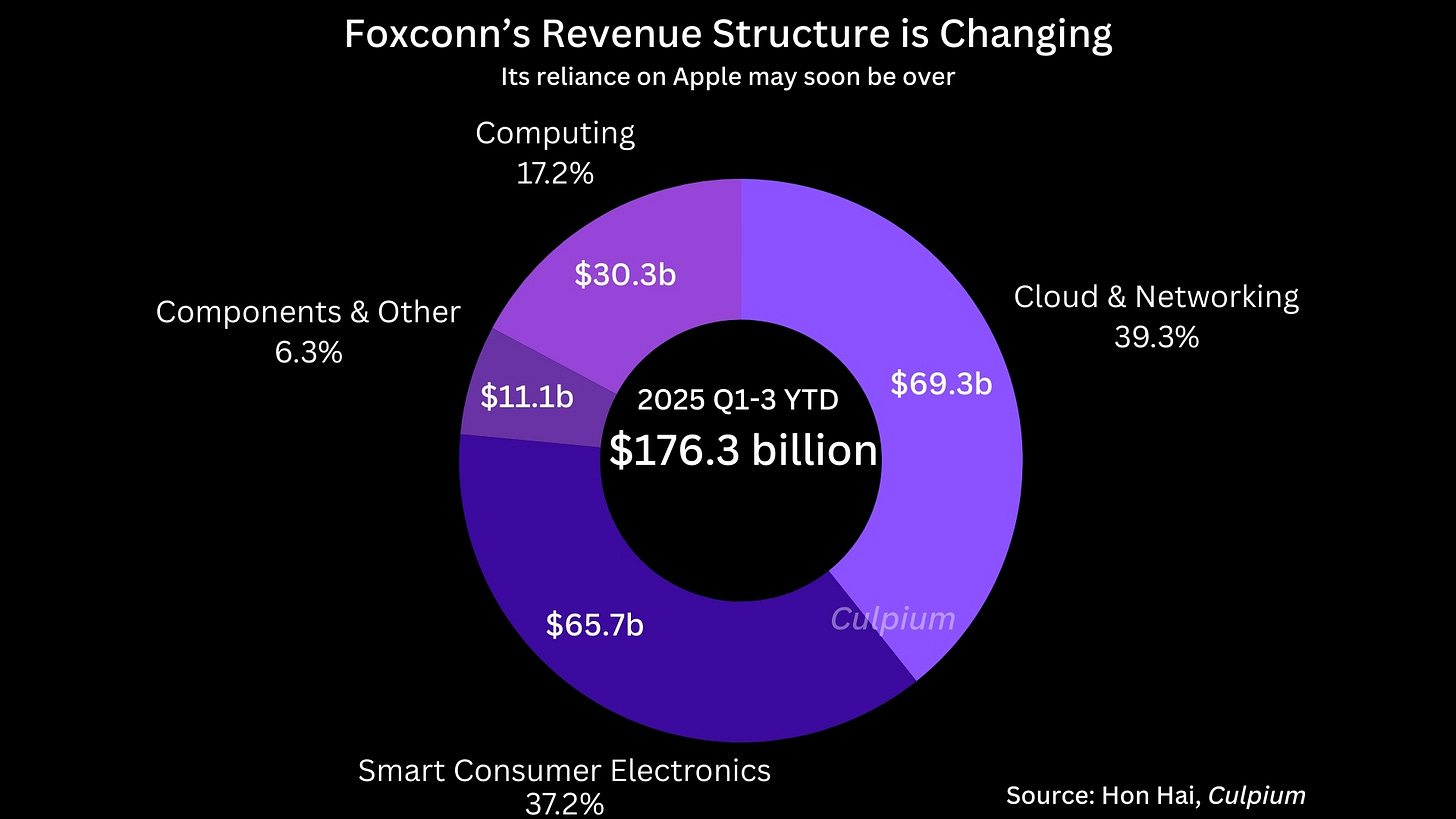

For the first time in more than a decade, smartphones are no longer the primary revenue driver at Foxconn. The Taiwanese company has been the key supplier for Apple’s flagship device since its launch in 2007. That created an unhealthy co-dependency for both companies.

Foxconn, however, has weaned itself off Cupertino much more than Apple has been able to wean itself off the Taiwanese company. Cloud & Networking products accounted for 39% of Taipei-based Hon Hai’s revenue over the first nine months of this year, compared to 37% for Smart Consumer Electronics. AI servers, largely those developed around Nvidia’s GPU ecosystem, are the major component of growth in the cloud & networking segment. Its consumer electronics segment includes smartphones, games consoles and tablets. Laptop and desktop PCs fall into the Computing category, while Components refers to those sold separately not including the vast number which are produced and sold in-house.

Foxconn’s new pitch to clients, and foreign leaders, is a redux of its original business model: we make all the ingredients that go inside your product. What’s different today compared to 20 years ago, is that the final products showing the most growth potential are much bigger, more expensive, and with far more components inside. I’m talking about AI servers, electric vehicles, mobile-phone base stations, and satellites.

A single Nvidia AI server sells for up to $5 million. You’d need to build and sell 4,000 to 5,000 iPhones to reach that level of revenue. More importantly, an AI server has more parts, and because of its size and design it is a better candidate for robotic assembly. This potential for automation is what allows Foxconn to be confident in its ability to scale up AI-server manufacturing in America, which it’s doing through its Ingrasys unit in Houston.

And, although many components, like sockets, plugs and cables, sell for just a few dollars — sometimes even pennies — they can also be made with almost no human intervention. I recall a visit to a Foxconn factory in China where PC-cable sockets were fed from a roll like film through a projector. Hon Hai affiliate Foxconn Industrial Internet is another unit with a plant in the Houston area.

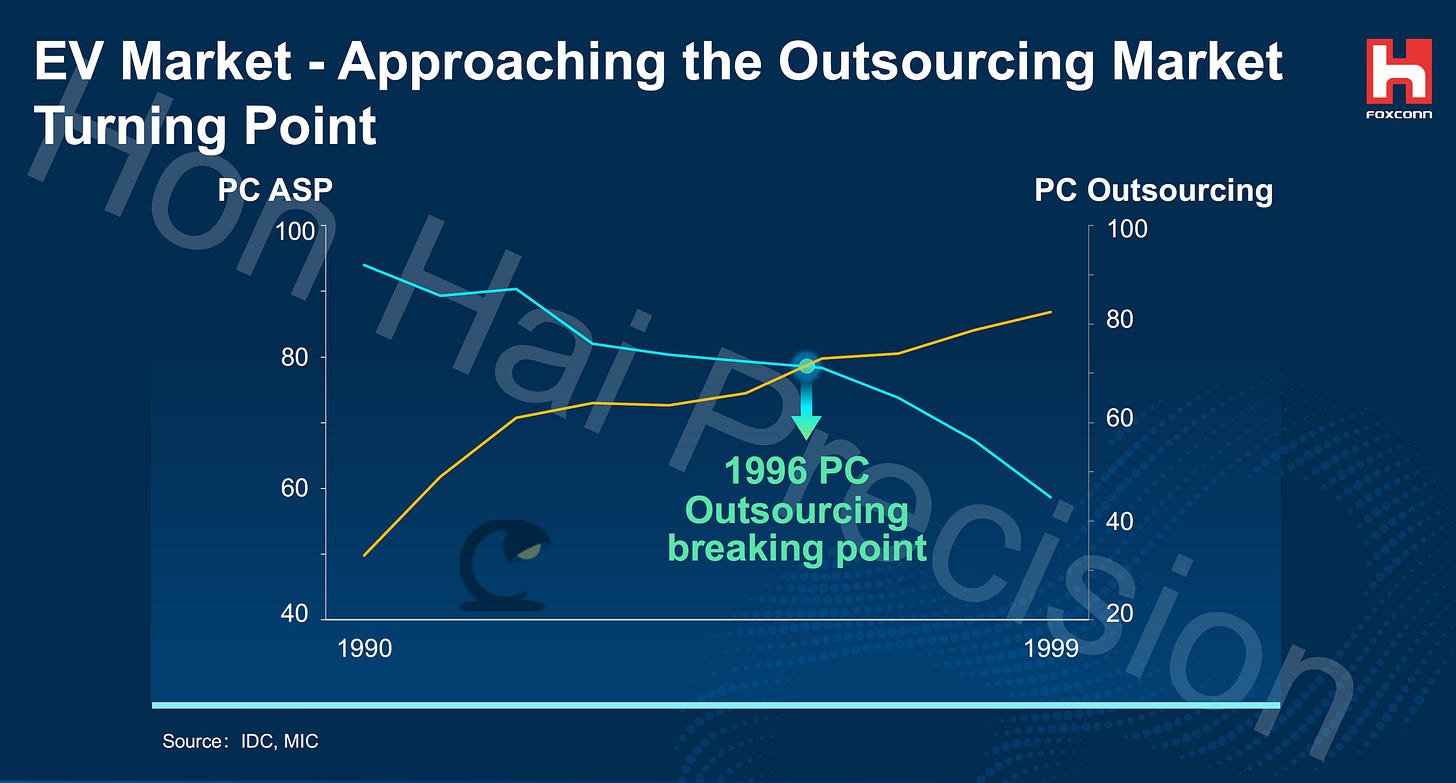

Liu has also made a big bet on EVs. He has many skeptics. And they’re not wrong. But we ought to remember that Liu’s been in the industry long enough to know how product-manufacturing changes with the times. There was an era, Liu recalled, when PC makers were proud of making their own computers. Today, they all lean on outsourcing. As prices fall, EVs will do the same, Liu argues. And even if Foxconn doesn’t actually assemble the car — which it can and wants to do — it’ll still be there to supply the thousands of components required. This goes right down to micro-controller chips that are designed by its unit SiliconAuto unit and fabbed at TSMC.

Satellites are another area of massive potential. The rise of private operators like SpaceX and Blue Origin has slashed the cost of launch. Apple has already built satellite connectivity into its iPhones, and it’s only a matter of time before more devices like smart watches also connect to the stars.

Development and production of satellites needs to keep up, which will increase the need to cut prices. Foxconn has already built and launched two satellites. A senior executive in charge of satellite development told me that Foxconn’s big push into this arena will come once the 6G mobile telephony specs are finalized, which is likely to include provisions for satellite communications.

As with PCs, smartphones, and EVs, low prices are Foxconn’s specialty. Not because of low-cost labor, as many imagine, but because of its ability to develop and produce most of the components that go inside, giving it unique vertically-integrated economies of scale.

One thing that US business and political leaders ought to note is that none of this need include China. Foxconn isn’t exiting that country, which remains its largest manufacturing base, but it sure is leaning on the world’s second-largest economy a lot less. None of the assemblers of Nvidia AI servers — including Foxconn, Wistron, and Quanta — are making them in China. Liu himself said recently that its US operations will serve the US market, its Taiwan factories will serve the rest of the world, and a new facility in Japan will add to global capacity.

This reconfiguring of global technology manufacturing presents a great opportunity for America. Smartphones aren’t going away, but buying cycles are slowing. Growth instead will come from new areas like AI servers, EVs, and satellites — products which don’t need massive labor-intensive factories. They do, however need companies with the skillset to both develop and scale-up manufacturing of the crucial components inside — where the real value lies — as well as the ability to run automated production lines which can put it all together.

What will come of this reindustrialization isn’t tens of thousands of low-skill American jobs, as is often discussed on the campaign trail. Instead, what’s on offer is the chance to create plenty of opportunities for technically adept workers. The US currently lacks adequate supply of staff for areas like molding, machining, and precision engineering. That’s not a problem because Taiwan has the fix.

Companies like Foxconn, Quanta, Wistron, SPIL, GlobalWafers and TSMC — all Taiwanese — aren’t coming to the US for the cheap labor. While political pressure was the catalyst, they’re really expanding onshore to tap into the potential for a workforce of trainable technicians that can learn new high-value skills. Over time, America can regain these lost arts, capabilities exported to China over the past three decades.

America’s prospects for reindustrialization are bright. It’ll need Taiwan to build that future, with Foxconn as one of the chief architects.

More from Culpium: