The World's Biggest VC is One of the Worst

[Opinion] SoftBank's Vision Fund is underperforming the S&P 500. It's OpenAI bet won't change that

Good Evening from Taipei,

SoftBank Group Corp. hasn’t yet seen a bandwagon it didn’t want to jump on.

The Japanese telco-cum-conglomerate is still riding on the coattails of its early investment in Chinese e-commerce player Alibaba, and once proudly crowed about throwing money at co-working startup WeWork. Now it is love-bombing OpenAI.

Where once SoftBank was enamored with Adam Neumann, now it seems management is besotted with Sam Altman.

It’s already been seven years since SoftBank founder Masayoshi Son did seemingly little due diligence on the way to making a big bet on Neumann’s WeWork. But it feels like yesterday, and the hangover still remains. Neumann’s venture went bankrupt and lost SoftBank more $6 billion.

It would have been easy to write this off as just a part of venture investing. It’s not.

The key problem is that SoftBank ridiculously overpaid for WeWork, buying in at the top of the hype and somehow believing that capital markets would take care of the rest. It did the same for Chinese ride-hailing company DiDi, and its fortunes remain tied to TikTok owner ByteDance.

You’d think that the lessons from WeWork would have chastened the Tokyo-based company. Not so.

Just one year after WeWork finally filed for bankruptcy, SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2 recently sank a huge chunk of its remaining funds into OpenAI at a valuation of $157 billion.

Its penchant for chasing high-flying, high-priced startups forms the backbone of SoftBank’s venture-capital strategy. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

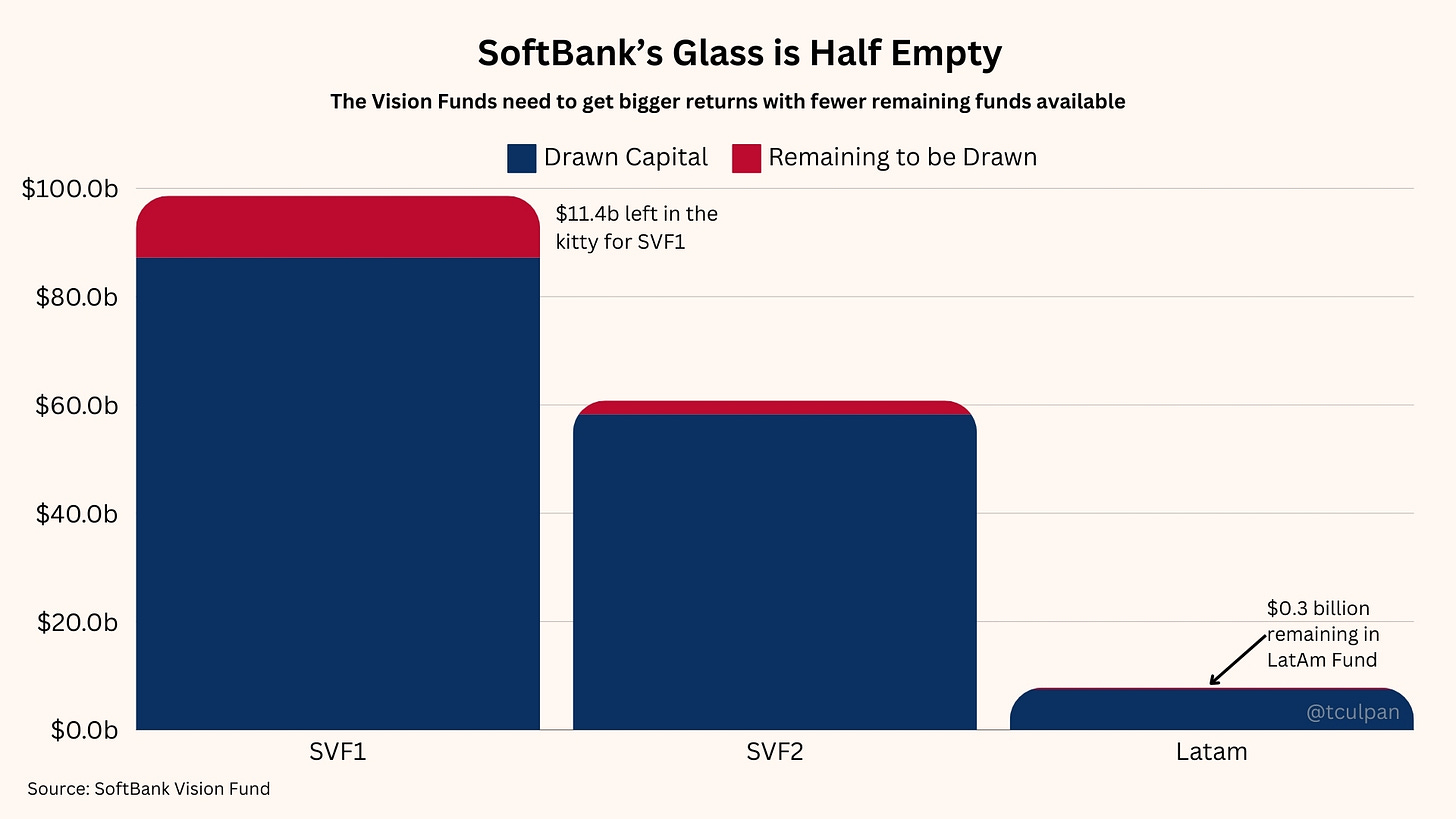

With $150 billion across three funds, SoftBank Group eclipses the next three pure VCs combined. The fun started seven years ago when founder Son launched the SoftBank Vision Fund, aka SVF1. Two years later came SoftBank Vision Fund 2, and it has a smaller Latin America fund.

But they’re terrible at what they do. Venture investing is hard. It’s not enough to pick winners, you need to get them at the right price. And this is where SoftBank has messed up.

A win rate in the ballpark of 10% to 20% is pretty good. That is, you can expect 8 or 9 out of 10 investments to lose money either because the startup failed, or the investor exited below their acquisition price. This ratio differs a lot between early, mid, and late stage, and the expected return varies accordingly. But if you get them at the right price, and the few winners hit home runs, then your fund makes a lot of money.

SoftBank tried to rewrite the playbook. It hasn’t fared well.

SoftBank’s win rate across its three funds was 25% by the end of September. That’s pretty good. Yet there’s two major problems with SoftBank’s approach. First, it focused heavily on late-stage investing. This is a legit strategy but brings survivor bias. Any startup which has lasted so long, by virtue of it still being alive, looks like a great company.

Second, because through rose-coloured glasses the target looks good, there’s a temptation to pay too much for a stake. And, again because of survivor bias, there may be a tendency to not ask too many questions. WeWork isn’t the only example. SoftBank’s Vision Funds have taken stakes in hundreds of companies, and the group fancies itself an AI connoisseur. In reality, it’s only made money in its consumer-sector investments and lost across its eight other tech-heavy categories including edtech, fintech, frontier tech and health tech.

As a result, SoftBank’s biggest fund — the $98.6 billion SVF1 — is up only 25% since its founding in 2017. By contrast US consumer prices climbed more than 28% in that time. In real terms SVF1 is underwater.

Given the risk-return profile of VC investing — including liquidity risk — earnings need to be better than what you get from a Vanguard S&P 500 ETF. Except, since May 2017 the S&P 500 returned more than 12% — per year. Investing $100 in the S&P 500 back then would have left you with $241 at the end of September. SVF1 investment provided less than $126. That’s before deducting “third-party interests, taxes, and expenses.”

SoftBank’s SVF2 and LatAm funds aren’t helping. SVF2, with $53.6 billion of investments, is down 39% since its founding in May 2019. The LatAm fund is relatively small, at $7.8 billion, and has lost 14%.

Compounding the problem is that SoftBank has already drawn on and deployed almost the entirety of the funds committed to it by investors. Being so far under water with little ammunition left makes it really difficult to pick the big winners needed to make up for past losses.

The Vision Funds aren’t the only thing SoftBank Group does. It holds a chunk of semiconductor-technology developer ARM, owns a telco called SoftBank Corp., and has holdings in other companies like T-Mobile. Management likes to talk about their big, grand, long-term vision in AI and green energy, and biotech, and maybe even DEI. Because these are all hip, and SoftBank wants to be hip. But you can invest in those yourself and don’t need SoftBank’s help.

It’s possible that SoftBank’s Vision Funds will recover: narrowing the losses at SVF2 and LatAm, and broadening the return at SVF1. But the numbers just don’t add up. It’s already exited more than $50 billion of its $150 billion to date. Another $27 billion of its investments have IPOed which means it’ll need to cash out of those soon, too. That means the remaining $70 billion or so needs to more than double in value if the funds are to return a barely respectable 50% return in aggregate.

Take OpenAI. SoftBank invested a mere $500 million. But for that bet to return a measly $1 billion to the Vision Funds, and boost the total return by just 0.7 percentage points, Sam Altman needs to drive the developer of ChatGPT, DALL-E and Sora to a near $500 billion valuation by the time it IPOs.

SoftBank might be so fortunate. But that would prove the point. SoftBank Group isn’t a reliably good investor, it just sometimes gets lucky.

Being a Big Stack Bully, as SoftBank has been labeled, works at the poker table. But in the venture world, where companies must eventually get valued by the market, bluffing isn’t a strategy. That’s the difference between investing and gambling.

Thanks for reading.

News & Analysis You May Have Missed: