AI Isn't the Doctor You Need in a Cancer Crisis

From feeding tubes to fentanyl addiction, my personal journey shows there are many aspects of cancer care that require human attention. We can't rely on AI to do the job.

“I have cancer.”

Those are the words that almost 20 million people across the globe utter to friends and family each year.

I am one of them.

That phrase first stumbled from my lips two days before Christmas 2024. The cancer was at Stage Three. It had already spread.

There’s no normal way to receive the news, no normal way to share it, and no normal way to deal with it. Life after a cancer diagnosis will never be normal.

One of the many things I learnt from my experience is that although 20% of people across the globe are likely to get cancer during their lifetime,1 each cancer patient’s journey is unique. And very, very lonely.

Cancer is like no other illness. The word itself is like a spider: a curiosity or annoyance at a distance, but utterly frightening when it lands on you. It requires ongoing attention but cannot merely be managed as a chronic condition like diabetes, lupus, or heart disease. It cannot be ignored. It needs to be defeated.

My diagnosis came as the artificial intelligence hype was ramping up. Instead of asking Google, patients are now turning to ChatGPT, Claude and Perplexity to answer queries ranging from cold remedies to cancer treatments. I quickly jumped aboard.

AI was great. Until it wasn’t.

Research shows that the best models risk clinical harm in around 15% of cases, while that rate is close to 40% for the worst models. Perhaps more worrying is that even with low, but non-zero, error rates there’s a risk of introducing bias: medical professionals start trusting AI over their own knowledge.

Another study outlined the limitations of using large-language models (LLMs) in healthcare. Among the fourteen issues identified by the authors were an inability to learn from experience, being unable to grasp context, and lacking emotional intelligence. “ChatGPT is unable to understand users’ emotions and cannot empathize with them,” they wrote. “It is not possible to understand the awkward glance by a patient.”

The Human Profession

This last point — emotional intelligence — is lost amid the hype over AI’s growing role in medicine. But it’s the single most important aspect of being a doctor, a nurse or even an orderly. Of all professions, ranging from law to landscaping, transportation to teaching, healthcare is the most human. No other occupation is more intimately connected to the very human experiences of getting sick, feeling fear, and dying.

My cancer assessment was first delivered by a forlorn-looking GP who kept uttering “sorry” between bouts of medical advice. She happened across the signs during a checkup for other issues and sent me off for scans. No image-recognition model could ever have spotted what an experienced doctor felt with her own hands, nor delivered the news with the compassion of an emotionally intelligent clinician. Besides, I couldn’t have coped with even the most human-like robot telling me I might die.

After sharing the news with family and cutting short Christmas celebrations, I went down the chatbot rabbit hole. Treatments, survival rates, side-effects and coping strategies were delivered with ease and confidence, as if a calm experienced doctor was on the other end of the chat. It didn’t help. It made me feel worse, more alone. More vulnerable.

But I couldn’t stop. Even after consulting human doctors — a hematologist, two oncologists, a surgeon — I kept on my AI crusade. I wasn’t doctor-shopping: each of these specialists had a role to play in my diagnosis and treatment, and there’d be more. I spent an entire day with Perplexity, digging out medical papers related to my specific brand of cancer, and printed out a four-page report to take to my medical oncologist. I felt like a diligent student who did all his homework plus the extra-credit assignment.

My doctor’s reaction was neither annoyance nor dismissal. He’d helped run clinical trials before and seemed genuinely happy that I was taking such an active interest in the research. I am a PubMed nerd, I told him truthfully. But with the patience of an elementary school teacher, he politely guided me away from the confident and hallucinatory directive I held in my hand and outlined my case for me. He even took the extra step of writing down journal articles more applicable to my situation, suggesting I spend time with them instead. AI wasn’t his enemy any more than Google was the enemy of doctors a generation ago, but such tools had limitations.

As chemotherapy got under way I quickly found out that the real medical care didn’t come from knowing my cancer type or the probability of survival - that’s just statistics. Nor was it from using a machine to inject precise doses of platinum-based chemical cocktails and sleep-inducing antihistamines. That’s just engineering.

It came from six-hour long sessions in the infusion ward, where my anxiety and panic collided with IV needles and the determination of a nurse patiently making her third attempt to find a vein. My medical care wasn’t delivered by an expensive high-powered proton therapy system. The care came from a kind and diligent radio oncologist who sent me back for successive 3D scans and precise tumor mapping, ensuring that six weeks of daily radiotherapy would kill the cancer but deliver minimal damage to healthy tissue.

Artificial intelligence systems may help aid diagnosis, plan treatment, or manage records, but they will never match a human’s ability to comfort and guide another human through the trauma and triumphs of being a frail, mortal human.

My radio oncologist has treated hundreds of patients, yet a moment when I most appreciated her experience came when she delicately guided two feet of rubber tube through my nose and into my stomach so that I could get the nutrition I needed. There are few things more inhumane than having to feed through a nasal-gastric tube for two straight months. A robot would never have completed that task, let alone done so with the care and empathy that she showed.

I had a surgeon, too, with that customary surgeon’s swagger. His constant missives of “don’t worry” at first seemed tone deaf. I had cancer, of course I was going to worry. But he knew something that no LLM could truly understand: to worry was a natural human instinct, yet utterly unhelpful. After months of fortnightly visits, including very worrying setbacks in my treatment, I started to imbibe his “don’t worry” mantra. I still worried. But less. There was something comforting about listening to a confident human instead of a confident chatbot. Perhaps it’s the warmth of the delivery or his genuine wish that I did truly have nothing to worry about.

My situation has stabilized. I’m confident I’ll survive. But it’s not over. I have months, even years, of post-treatment therapy to combat what could be life-long side effects. Still, I am one of the lucky ones.

A large portion of my luck comes from having affordable access to world-class healthcare. My consultation and treatments were undertaken in a first-world nation at a medical center paid for by a billionaire — Foxconn founder Terry Gou, who lost both a wife and brother to cancer. My radiotherapy was provided by Varian’s cutting-edge Proton Therapy systems which Gou also paid for. Dozens of my fellow cancer victims enjoyed the same privilege, and it is a privilege. I saw many of them with my own eyes, as we waited robed and silent for our turn to be strapped down and zapped with beams of radiation. I know that many of them won’t have made it. Survivor’s guilt is real.

Burden of Poverty

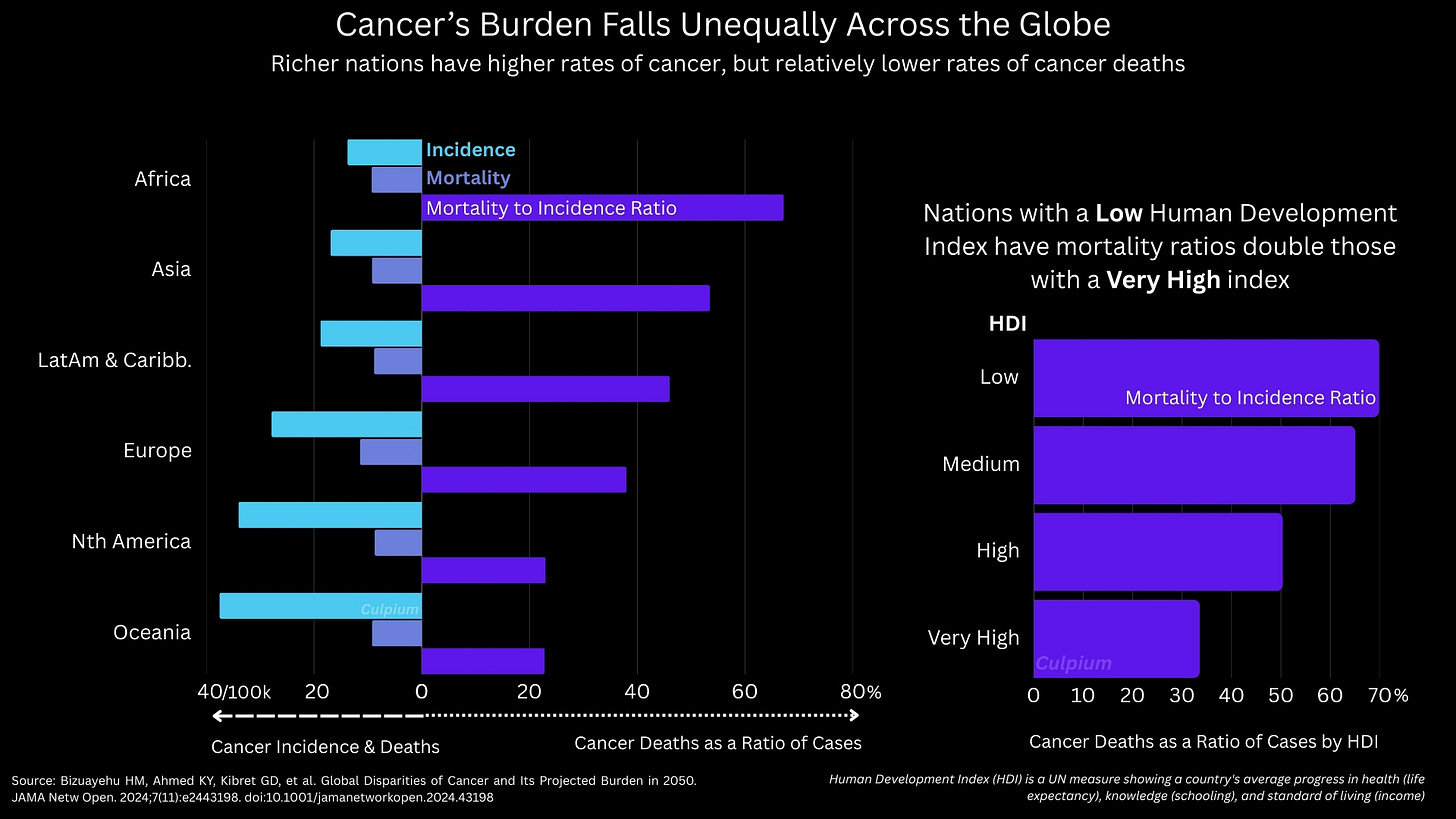

Around 18.5 million cancer cases were registered globally in 2023 and at least 10.4 million died. That’s 56% of the number diagnosed, according to data published by The Lancet.2 Of course, each type of cancer has its own survival rates. These in turn depend on factors beyond the cancer type, such as the stage of diagnosis, age, general health, race, and the presence of other diseases (comorbidities). Yet data shows that the biggest factor is access to medical care.

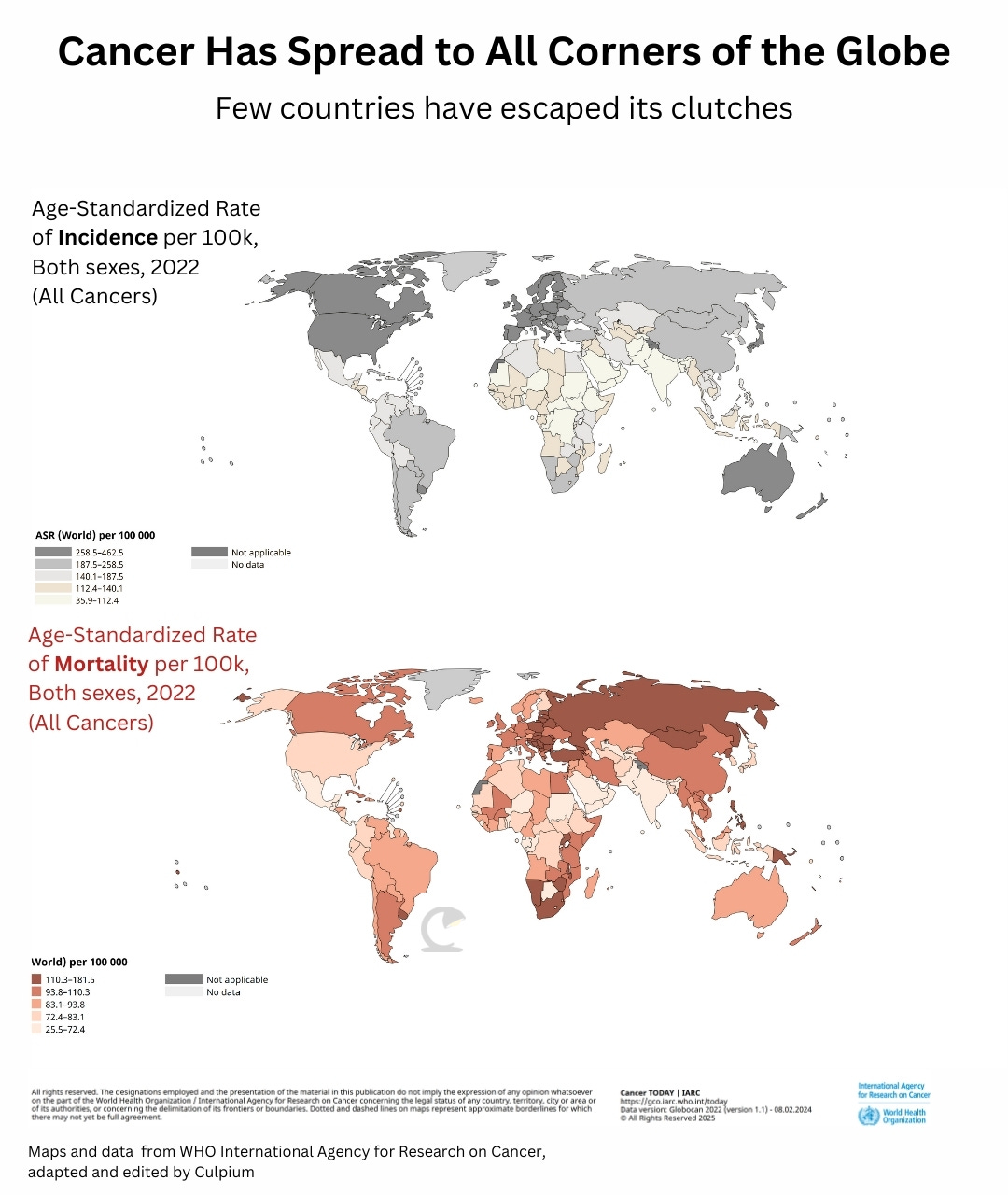

Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, and the US have the highest rates of cancer per capita in the world, but they’re nowhere near the top of the list when it comes to actually succumbing to the disease, according to WHO data. Mongolia and Zimbabwe have that distinction.

Despite advances in medical research, cancer rates are expected to climb by more than 60% over the next quarter century to 30.5 million annually. Deaths could rise 75% to 18.6 million, “with over half of new cases and two-thirds of deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries,” the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation wrote, citing The Lancet paper.

Those last two facts are astounding: Half of new cases, but two-thirds of deaths.

Cancer’s burden will disproportionately fall on the poor: those who can least afford the prohibitive cost of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery and the myriad pre- and post-therapy treatments that come with it. It’s because of this cost, and lack of access to general healthcare, that poor patients will die at a disproportionately higher rate.

Global access to artificial intelligence tools, including large-language models, may be able to ameliorate this inequality. It’s worth noting that when I asked, none of my doctors expressed objection to AI’s role in medical care. One oncologist noted that they subscribe to multiple LLMs while remaining wary of hallucinations and false information. They recalled one instance where a patient faced complications that couldn’t be easily pinpointed. A “conversation” with ChatGPT helped brainstorm ideas, helping the doctor diagnose the root cause and find a solution.

Yet we mustn’t misunderstand the power of AI in diagnosis. A paper published by Microsoft in June titled “The Path to Medical Superintelligence” trumpeted the US software company’s “model-agnostic orchestrator” which simulated a panel of physicians in a diagnostics competition against human clinicians. At first blush the results sound impressive. But upon closer inspection, the exercise was flawed. The model was testing only against known cases published in the New England Journal of Medicine, yet it undoubtedly was trained on those very papers. The humans, on the other hand, weren’t allowed to search the internet nor consult with colleagues — both unlikely scenarios. Microsoft’s offering, in other words, was a souped-up search engine. The original diagnoses came from human doctors in real-life clinical scenarios.

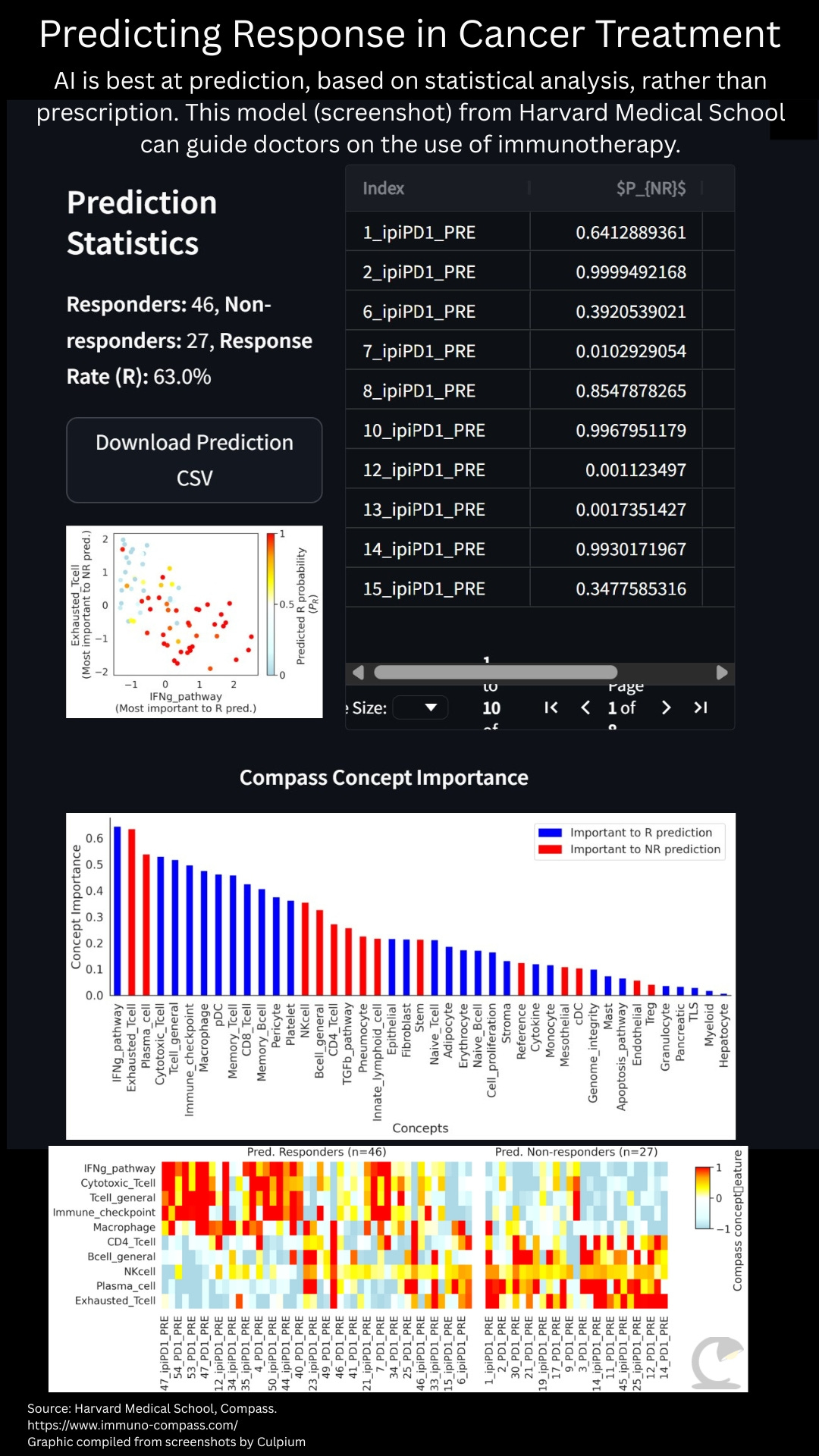

A more impressive AI system is the Compass model developed by researchers at Harvard Medical School and outlined in a paper titled “Generalizable AI predicts immunotherapy outcomes across cancers and treatments.” In this case, the team fed thousands of data points on tumors, immunotherapies, and outcomes into a computer. Their model then allows doctors, or even patients, to upload data from a tumor’s RNA to predict the likelihood of response to immunotherapy.

In addition to chemotherapy, which is a common frontline treatment for many cancers, the fields of immunotherapy and gene therapy have popped up to more carefully target tumors. But neither immunotherapy nor gene therapy are applicable in all circumstances. At present only a small cohort of tumors, such as some which show expression of a protein called PD-L1, are likely to respond to immunotherapy. Yet, because immunotherapy recruits the body’s own immune system to fight cancer there can be significant downsides in its use. It’s also very expensive. Being able to predict which tumors might respond can be crucial for doctors and patients to make better choices, and save money.

Gene therapy faces similar challenges, notably in the lack of druggable targets in many cancer types. With AI being used to fold proteins, surface new drug candidates, and test efficacy, there’s every chance that the cost and time to develop new therapies can be reduced. That also means offering up a wider array of drugs, including for rare cancer types that have so far escaped attention by pharmaceutical companies.

AI advances, driven by greater computing power crunching reams of data, can help healthcare workers and their patients in both first- and third-world nations. As the internet did with the digital divide, AI has the potential to help bridge the healthcare divide.

But AI cannot replace the people actually providing the healthcare. To believe otherwise is misguided, if not dangerous.

LLMs, the most common interface people currently have with AI systems, should never be viewed as a proxy for human doctors. Personal medical advice and treatment is not where we should place our hopes on AI for healthcare advancement. As with blood tests, X-rays, and MRIs, they should be seen as tools to help us identify problems, not solve them.

The Human Disease

Cancer, as one of humankind’s most insidious and confounding diseases, shall serve as the test case for how we both embrace and guard against the advances of artificial intelligence.

I’ve been there. I’ve seen what AI can do, what it can’t, and where the pitfalls lie.

An AI model, for example, can tell you that many cancer patients choose to forego treatment in favor of a quicker death. But it cannot explain why. A doctor can. They’ve seen it with their own eyes, heard it with their own ears. Felt it with their own heart. They instinctually understand that an achievable end to the darkness is far more enticing than a slow, exhausting recovery that for most will never be fully over. For some, it will never even come. A patient is not trying to avoid the pain — which is well-mitigated by a vast menu of legal opiates — they’re seeking to rid themselves of the loss of control and lack of agency. An AI model is no help here.

If anything, the cold scientific truths delivered by an LLM compound the pain. Most patients will suffer from the effects of their treatment for years, “many of those symptoms will remain forever,” a chatbot will tell you. What it won’t say is that these symptoms serve not only as a constant reminder of the near-death experience, but as an incessant warning that at the cellular level there’s a time bomb that may start ticking again at any time. No one wants to live under that cloud, no matter how much Joie de vivre remission inspires.

And with such “helpful information” about post-treatment side effects just a keystroke away, even the hardiest survivor could be justified in believing that their life has peaked with little good ahead. The most intelligent generative pre-trained transformer still lacks the EQ to convince a patient otherwise.

Although often hallucinatory, GPTs are logical by design whereas humans are primarily emotional, by design. I’ve not known any of my doctors to tell a lie, even a white lie, but bad news has always been delivered with compassion and helpful advice. Maybe it’s just a look in the eye or the tone of voice, but in moments of uncertainty these little human inflections mean the world.

A human doctor can also give very human responses to very human frustrations. It was my radio oncologist, for example, who suggested a swig of olive oil to offset radiation-induced dry mouth. AI hadn’t ever thought of it.

One of the toughest phases of my treatment and recovery was battling Fentanyl addiction. Administered through skin patches, the drug was the highest rung I climbed on an opioid ladder that began with Tramadol. I commenced my therapy determined to avoid opioids in the naive belief that Ibuprofen would be enough. I caved. But after the effects of concurrent chemo-radio therapy subsided, the feeding tube removed, and the skin on my face and neck stopped melting off, I was left an addict. The pain had gone, but a day without Fentanyl left me jittery, sweaty, and sleepless.

When I went to my medical oncologist with an AI-delivered prescription for kicking my Fentanyl habit he noted that these were no better than the drug I was already hooked on. Each of my AI chatbots had assured me this combo was standard treatment for opioid addiction. My doctor had a much better, more human prescription: sleep through it. Since I wasn’t working, I could afford to doze my way through withdrawal with the help of Xanax. This was the solution that I, a human, needed. And one which only a human had offered.

In moments of darkness — when I couldn’t eat, couldn’t speak, and could barely breathe — humans were my only salvation. I am very tech savvy: I’ve been a tech journalist for two decades, and have a Masters’ Degree in computer science. Gadgets and code are my comfort zone. Except when I was physically and emotionally uncomfortable. I didn’t want to search online for data and answers any more, I became repulsed by the robotic and false warmth of AI apps. It no longer mattered whether they were right or wrong, I could only feel their coldness. I found warm comfort bingeing episodes of Suits, because although fictional it seemed that human drama was still preferable to digital compassion.

In aggregate, my case was dealt with by more than ten doctors and over two-dozen nurses, in addition to medical technicians, orderlies, hospital volunteers and admin staff. I listed each person involved in my treatment and made a dispassionate analysis of which could be even partially replaced by some kind of AI, automation, or robot. Less than five, I concluded: mostly lab technicians or administrators.

Even if I peer into a crystal ball at where developments in artificial intelligence will take us in the next 25 years, I am certain that AI will not adequately replace a single one of the front-line medical workers who nursed me through the pain, the trauma, and the mystery of cancer.

But I also have a word of caution for the doctors and nurses who practice their craft with diligence and passion:

Lean into your humanity. Don’t fall prey to the mathematical algorithms which we now call AI. Humans are not statistics. To any individual patient it doesn’t matter whether a certain treatment for a given condition is 75% effective or 25% effective. For that one human, it’s binary: they’ll live through it, or they’ll die.

In my case, the odds were well in my favor when therapy commenced but started turning against me when early treatment failed and new drugs needed to be recruited. I still feel unsure. Doctors should always keep in mind that the one patient in front of them right now might be the edge case, the statistical outlier — for better or worse. But to that person, and to their family and friends, they are wholly unique. Each patient needs to be treated as an N=1 case.

All of us. Healthcare workers, patients, technologists, and policymakers also need to remember the most important fact of all. AI and medical professionals can both offer information, and both can make mistakes. But to care is human.

Thanks for reading

I plan to take a break for a couple of months. Things aren’t as dire as my last hiatus, but I need some time for recovery and rest. Thanks for your support this past year. May you have a healthy and happy festive season.

Primary data is for 2023 from the Global Burden of Disease Study Cancer Collaborators, published in The Lancet. Volume 406, Issue 10512 p1536-1537, October 11, 2025. Given trends, it’s assumed 2025 figures will be higher. Data excludes non-melanoma skin cancer.

Further data from: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services

This is known as the mortality to incidence ratio: 10.4m died of cancer in 2023, 18.5m were diagnosed, hence 56%. However, it’s not so simple: few fatalities occur in the year of diagnosis. Most survive many years before passing from the disease.

My mom also had cancer (long ago in 2007). She started with private hospital but the bills ruined our family to the point of bankruptcy then she had to go public hospital with the same doc. Your chart is true about Asian countries, it’s really worse here.

Eventually she misunderstood her treatments & care , she overdosed the pills they gave and her body got so weak that the cancer won. The cancer was worse even before the pills.

I don’t know if AI would have helped today, prob not too. Human care - doc, nurses, specialists, etc -is very much the key.

Hope all goes well with u & thank you for sharing.

Man, what a journey. Thanks for sharing this, Tim. And Godspeed.