This AI Bubble is More Memory Than Dot-Com

[Opinion] Massive capex is going toward factories that are churning out an ever-cheaper commodity. Pets.com was healthy by comparison.

Good Evening from Taipei,

Yes. We’re in an AI bubble. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. As Ben Thompson recently outlined at Stratechery, there are benefits to bubbles. The upside of the dot-com boom and bust was that it brought a whole generation of people online. Its related fiber-telco bubble gave us a global network of high-speed internet cables.

But this one is different in some fundamental ways. I think the remnants of a burst AI bubble will leave the world very different to what many currently imagine.

Here’s how I define a bubble:

Company valuations that are not supported by the revenue and profits they create,

Potential for a massive devaluation,

Impact from that devaluation.

Each is both objective and subjective since you can make up your own objective benchmark based on your subjective view of what the metrics ought to look like.

Yet an important trait of a bubble-and-bust is how the whole saga was funded. Andrew Ross Sorkin, who just published “1929: The Inside Story of the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History,” argues that debt — aka leverage — is what underpins impact. He outlined his thesis in a recent episode of the Odd Lots podcast with Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal.

“You actually can have speculators and all the bad actors you want doing all the bad things you can imagine on stage, but it’s the leverage that tips it over,” Andrew Ross Sorkin.

This hadn’t occurred to me, but seems so obvious once he said it out loud.

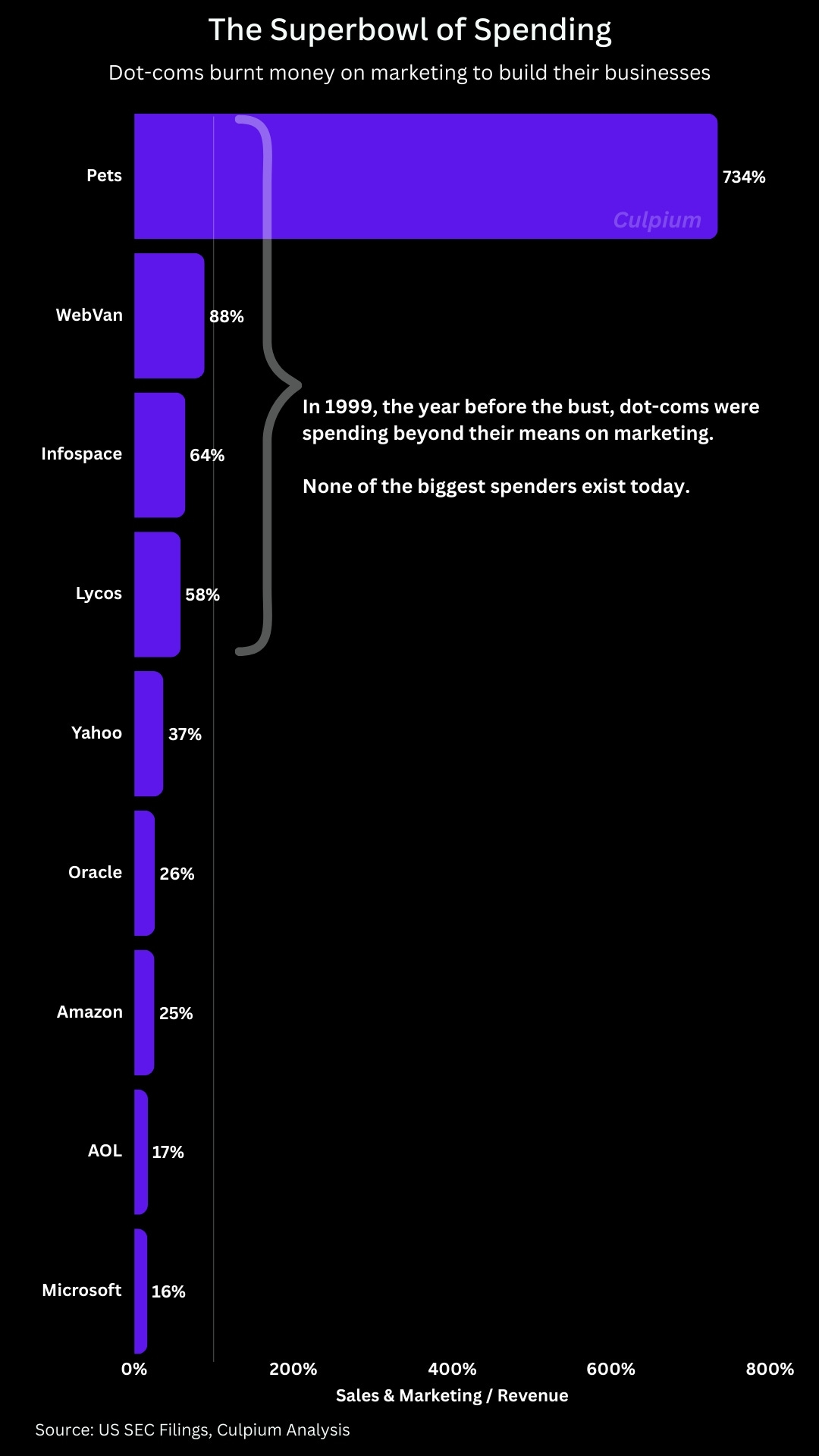

I spent a lot of time examining the dot-com crash of the early 2000s. This involved not only reading through the narratives of that time, but analyzing the financials of some marquee names of this era including Yahoo, Lycos, Webvan, and Infospace. The one company which represented the boom and bust of the era was Pets.com which died in November 2000.

In examining Pets.com’s financials for the period just prior to its bankruptcy, it’s hard not to think of Open AI founder Sam Altman’s recent reply to a very reasonable question. “How can a company with 13 billion in revenues make 1.4 trillion of spend commitments?” Brad Gerstner asked in his B2g podcast in early November.

“First of all, we’re doing well more revenue than that. Second of all, Brad, if you wanna sell your shares, I’ll find you a buyer … Just, enough!,” Altman replied.

Altman seemed annoyed by the question. But his OpenAI today is far less sturdy than Pets.com was back then. Dot-com companies, the story goes, were forced to spend a lot on capital expenditure as the bubble inflated, and then died because of this capex burden when the bubble burst. The data doesn’t back this up.

Capex in the year immediately prior to the March 2000 collapse averaged just 15% of operating expenses across a collection of representative stocks I collated. Pets.com’s capex was equal to just 22% of opex. To blame massive capital expenditure for their downfall is just wrong.

Instead, we need only look at how much they spent on marketing to get an understanding of what went awry. The median of sales, general and marketing expenses across this basket of dot-coms was a crazy 80% of sales, and that’s before accounting for R&D. Notably, Pets.com spent seven-times more on marketing than it received in revenue.

The underlying thesis of these internet companies was correct. Pets.com, for example, was right to believe that online commerce was the future. The problem was that dot-com CEOs were playing a game of chicken with their marketing budgets. The fear was that if they stopped spending on ads, discounts, and incentives then they’d fail to onboard enough customers and thus miss out on the future revenues which would justify all that spending. That’s just Startups 101, op. cit. Uber and Airbnb.

We are now seeing the same with AI companies. If any of them blinks, they risk falling behind and losing market share. Except they’re not spending billions of dollars on Superbowl ads, that money is going toward Nvidia-based servers and the massive data centers required to power, cool and connect them. You can cut your ad spend overnight, but capex is a much bigger commitment and lingers for years. Even if companies cancel their huge server orders at the first sign of trouble, the depreciation expenses will weigh on income for a while yet.

Also analogous to the AI bubble is the network-fiber boom which happened at a similar time yet had different characteristics. Builders and owners of intercity and subsea cables like Global Crossing, Williams Communications, and WorldCom spent billions to connect the world. Unlike dot-coms, these were capex-heavy businesses. Global Crossing’s capex was 1.3-times opex while Williams’ was at 70%. The multiples were even worse when compared to revenue. In the end, they each had massive infrastructure but lacked the operating cashflow to service their debts and went bust around 2002, two years after the dot-com bubble burst. This is the leverage Sorkin speaks of.

The dot-coms were low-capex, high-marketing consumer companies. The fiber telcos were high-capex B2B infrastructure companies.

Today’s AI companies have traits of both categories, but fit in neither.

Startups like OpenAI and Anthropic spend massive amounts of money on infrastructure, while established players like Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, Alphabet and Oracle are doing the same.

Hamilton Helmer’s framework on the 7 Powers of business strategy is a common lens through which to look at a company’s strength. Ben Gilbert & David Rosenthal of the Acquired podcast often use it to evaluate the quality of a deal.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: cheaper as you get bigger, keeping others out.

Network Economics: increased user value as more customers use it.

Counter Positioning: a different approach which incumbents won’t try.

Switching Costs: too hard to move to a competitor.

Branding: name alone adds value.

Cornered Resource: exclusive or preferential access, could include patents.

Process Power: secret sauce which makes it cheaper or better.

I doubt that OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, xAI, or Google have many of these. While they benefit from scale economies and cornered resources, they all benefit from economies of scale. Any cornered resource is likely to be temporary (a few years, at best). More importantly, none have true brand value and switching cost is non-existent. Like the incentives offered in the heyday of online commerce, users will swap seamlessly as soon as they find better value elsewhere.

As a counter example, we cannot deny the brand value of Apple and Samsung, or even iOS v Android. In addition, while it’s annoying to switch from Windows to MacOS — and a little easier to shift between Android and iOS — there’s no doubt that the lack of compatibility keeps consumers within one ecosystem or the other. This friction doesn’t exist in current AI models because early adopters can, and do, switch as quickly as they change browser tab. And I’ve seen nothing to suggest that any AI company currently has process power or gain any benefit from network economics.

Fiber telcos did have some of these powers, because not just anyone could lay down a cable at any time, and it wasn’t particularly easy to switch between network providers. As with the railway boom, the fiber companies built a lot of transport infrastructure which they kindly left behind even after going bankrupt.

But, fiber telcos also enjoyed very long depreciation schedules of up to 25 years. That means a $2.5 billion outlay appears as a $100 million annual cost on the income statement. AI companies have just trimmed their depreciation schedules to five years, from seven, so that same upfront payment appears as a $500 million annual charge. More importantly, thanks to Moore’s Law and a need to technologically “keep up with the Joneses,” AI servers near obsolescence in just a few years.

As a result, AI companies need to keep spending billions of dollars on fast-depreciating equipment to make a commodity product: tokens. These are the individual units of data used to process and analyze a request.

The label “AI factory” popped up in late 2024, and perfectly describes the server farms used to churn out tokens. I first heard the term when Foxconn Chairman Liu Young-wei explained it to reporters after announcing he was teaming up with Jensen Huang’s Nvidia to build the world’s largest AI factory in southern Taiwan. And if Foxconn’s getting involved you know commoditization is underway.

I’d argue that the ChatGPT interface, as it stands now, is rudimentary. It offers little more than a ticker of tokens, churning out responses that are just elaborate search results wrapped in prose. Google’s integration of Gemini into Colab, for example, makes it more app-like and functional. Search, to be sure, is lucrative as Google can attest, but ChatGPT is hardly counter-positioning. Right now, OpenAI is largely in the business of making AI tokens.

AI company founders may cling to the claim that they’re offering something unique, special and non-replicable. But as AI models develop, the gap between them is likely to narrow and users will find themselves seamlessly switching at the token level. The true differentiation is how they are applied — the application layer. But as we saw with DeepSeek — which “borrowed” tokens from OpenAI — this doesn’t require massive investment in token-making. Tokens will always be needed, and we’ll always need more of them, but the tokens are like the oil fueling AI applications.

This business of token-making involves massive capex, a commodity product with declining prices, minimal switching costs, fast-depreciating assets, and rapid pace of both manufacturing improvement and technological development. That’s not at all like oil, in fact it’s more like memory chips — both DRAM and NAND. You have both inside your computer (and cellphone), but I bet you don’t know the name of the supplier. And on a desktop (and many laptops) you can easily swap out or upgrade.

The only way for a memory-chip maker to survive is to keep investing in new equipment in order to both expand capacity — thus enjoy economies of scale — and improve technology, in order to stay competitive and keep customers upgrading. In memory, the tech specs which define competitiveness are capacity and speed. Both require the newest chipmaking equipment.

If you want to manufacturer the best chips, you need ASML’s EUV machines, and if you want the best AI servers you need Nvidia’s chips. Which makes Nvidia the ASML of AI. Conversely, if you do not pay top dollar for the best equipment, you’re unlikely to have the best product or be cost-competitive.

Since the AI sector at the model and token-making level is just like memory, the industry shakeout is likely to play out in the same way. DRAM used to be a big deal. For a while it was Intel’s bread and butter. These chips are fundamental to any computing system because they temporary hold data — often for milliseconds — which a processor uses to make calculations. In the early PC era, DRAM supply was the bottleneck for computer sales.

By the early 2000s, there were around a dozen memory-chip makers across South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and the US. Most were backed by industrial conglomerates. Hynix, for example, was spun off from the Hyundai group after the chaebol’s boss realized electronics were an increasingly important part of cars. Nanya Technology was born out of Taiwan’s massive Formosa Plastics Group. But heavy competition, unstable earnings, and an unwillingness by corporate parents and banks to keep funding them lead to a wave of consolidations and shutdowns by the early 2010s. Today, the DRAM sector is dominated by just three companies: Samsung, SK Hynix — both from South Korea — and Boise, Idaho-based Micron.1

What kept the leaders atop the market was both an unrelenting pace of capacity expansion, and continued technological development using the latest equipment. Both are crucial to maintaining price competitiveness on a per-bit basis. Assuming the product is largely reliable, price is the factor which truly differentiates.

Today’s AI leaders can be sorted into two categories: stand alone, and conglomerate-backed. OpenAI and Anthropic are startups that stand alone. A recent series of circular deals muddies the water a little: Nvidia is taking a stake in Open AI2, while the startup has a warrant for shares in Nvidia rival AMD. And Microsoft’s relationship with OpenAI makes the software giant as much a sugar daddy as a conglomerate parent: it’ll last as long as Microsoft’s AI friend provides benefits.3 These companies are kind of like Micron. Although it found a wealthy industrialist to back it, Micron never benefited from having a conglomerate parent.

Microsoft’s relationship with OpenAI makes the software giant as much a sugar daddy as a conglomerate parent: it’ll last as long as Microsoft’s AI friend provides benefits.

On the other side we have Meta, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Oracle and a few more. Some of these are building their own foundational models, some are distilling other people’s models, and others yet are just riding the AI wave by providing compute and network capacity. They are like Samsung, which comes out of a chaebol of the same name, and SK Hynix — itself the merger of two chaebol children. Oracle is the most leveraged to AI to a degree that is unsettling. It also has the least-varied revenue stream compared to the advertising, SaaS, and cloud offerings of its rivals.

Once the current bubble bursts, and the funding stops, AI companies will be faced with a tough predicament. As for the memory industry, those with big corporate backers have the best chance of surviving. They can slow investment and preserve cash, but risk falling behind both in capacity and technology. Or they can continue to play capex chicken, hoping a rival will flinch first. The stand-alone players will have fewer options. If the funding gravy train has already slowed, then absent continued cash from banks and corporate FWBs, they’ll need to either pivot or get acquired at a steep discount to their heady valuations.

AI is here to stay, just as railways and the internet still endure. That doesn’t mean we’re not in a bubble. It also doesn’t mean all of today’s AI leaders will survive this boom and bust cycle. Application developers— those who make use of AI models to boost productivity, reduce costs, or create entirely new product categories — will define the future. But many model makers will be wiped out.

What will be left is a handful of AI factory operators churning out cheap tokens to feed the long-march toward AGI.

Thanks for reading.

More from Culpium:

The NAND sector is slightly more competitive; Counterpoint has a breakdown.

Nvidia took a stake in a 2024 funding round, and pledged to up that stake over time in a separate deal announced in September 2025.

Microsoft has a 27% stake in OpenAI, in addition to cooperation at other levels.

AI distills the collective wisdom of a whole bunch of people into an interaction that appears to be occurring with a single person. It’s the opposite of the network effect.

I agree, we are in bubble territory. Three years in and OpenAI's bleeding $12B per quarter while 95% of users pay nothing. Anthropic breaks even by 2028, Google doubled market share in 12 months. The memory chip comparison nails it - tokens are commoditizing faster than OpenAI can figure out how to charge for them.

But your article misses something: the differentiation already moved up the stack. Claude Code has 42% developer share vs OpenAI's 21% not because of better tokens, but because it's baked into how developers actually work. Switching costs show up at the workflow level, not the chatbot level.

And Anthropic's path to $70B revenue with 80% enterprise proves you don't need a consumer circus to survive - you need customers who'll actually pay. OpenAI's building factories to make a commodity product while their competitors are building the applications that matter.

800M users is a vanity metric when you're burning $1.4T in compute commitments you can't monetize.