This AI Bubble is Now Flashing the Granddaddy of Bearish Signals

[Opinion] Paul Tudor Jones is among investors who see the 200-day MA as a metric to track. It's now showing warning signs for a number of AI players

Good Evening from Taipei,

Something happened last week which I think is worth sharing. A key indicator of pricing trends across a basket of AI stocks flipped to the downside.

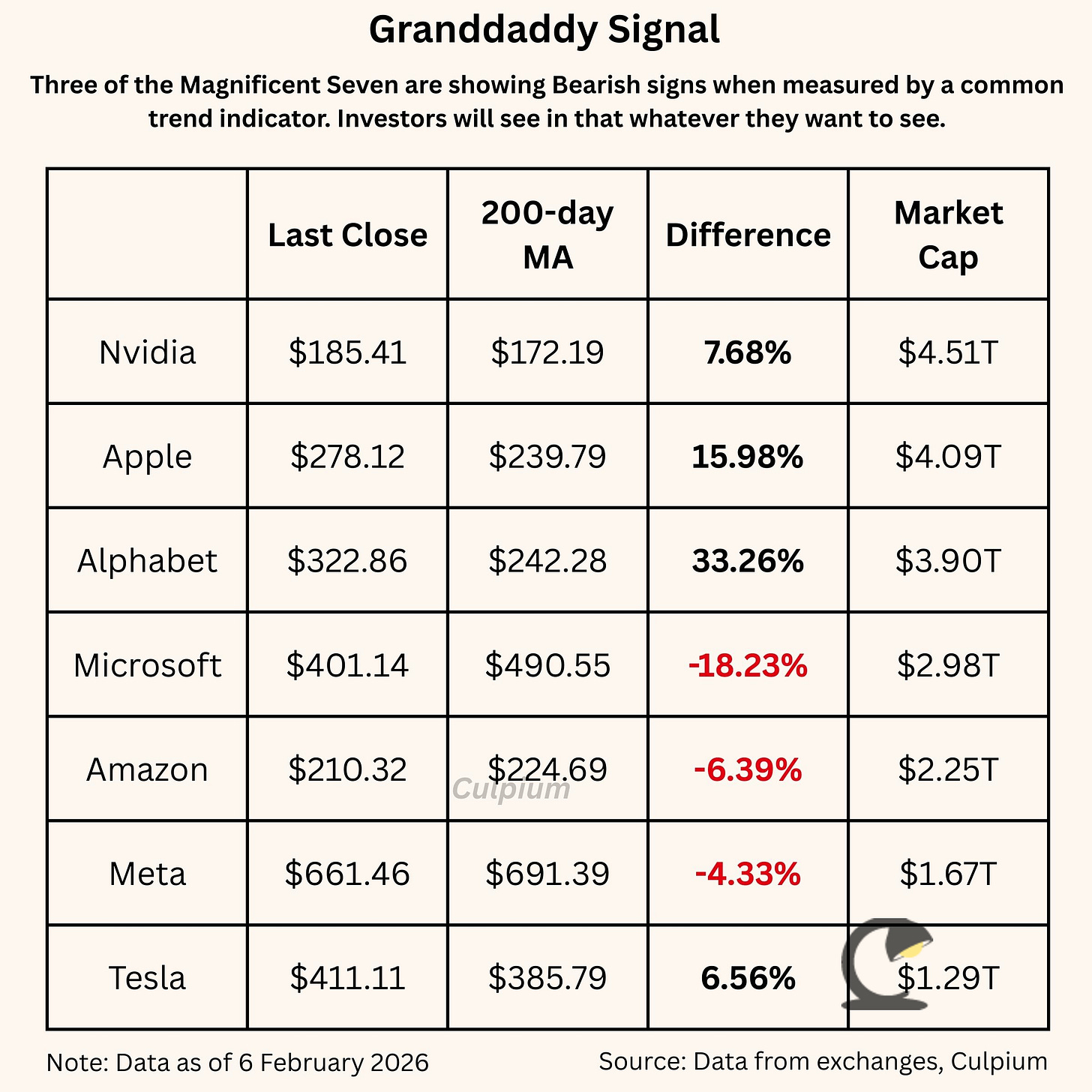

Three of the Magnificent Seven closed below their 200-day moving average last Friday. Those companies are Microsoft, Amazon, and Meta. The other four members — Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet and Tesla — remain above their 200-day MAs.

I have been tracking this indicator since November 2025 after Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway interviewed Dirk Willer, the Global Head of Macro Strategy at Citigroup, for an episode of their Odd Lots podcast. Willer uses what he calls the “Generals’ Framework,” meaning to look just at the leaders to assess whether or not the AI bubble has burst.

We look “just at the top seven leaders because people are excited about the mag seven,” Willer told Joe and Tracy in the Nov. 15 episode. “If three of the top seven breakdown, meaning they fall below the 200 moving average, that's a really dangerous sign.”

By the close of trade Friday Feb. 6th, Microsoft was 18% below its 200-day MA, Amazon was 6.4% lower, and Meta 4.3% below.

Willer isn’t the first to use the 200-day MA as a guide to bearishness, and thus a signal to take your money and run. Famous hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones used this as his benchmark, according to comments he gave Tony Robbins for the book “Money: Master The Game,” earning it the nickname the Granddaddy of signals.

“My metric for everything I look at is the 200-day moving average of closing prices. I've seen too many things go to zero, stocks and commodities,” he was cited as saying. “If you use the 200-day moving average rule, then you get out. You play defense, and you get out.”

Willer noted in his chat with Joe and Tracy that the Magnificent Seven is somewhat arbitrary. It could be the top-10 stocks in a category, he said, but the point being that you look at the leaders. The Mag Seven, being both big and indicative of the AI category, are as good a benchmark as any. In truth though, Tesla could be replaced by Oracle if we’re tracking AI stocks. In that case, Oracle’s recent slide puts it 35% below its 200-day MA.

Amazon’s sell off came after it reported earnings and then forecast massive expenditure to meet what executives believe will be growing and continued demand for AI services.

“We expect to invest about $200 billion in capital expenditures across Amazon in 2026, and anticipate strong long-term return on invested capital,” CEO Andy Jassy said in a Feb. 5 statement. It spent $132 billion last year and analysts had expected $146 billion in capex for 2026. Just a day earlier, Alphabet signalled it may double its own capex to as much as $185 billion. A week earlier, Meta said it’s AI-related spending could be as much as $135 billion.

Overall, four of the biggest US tech companies are set to spend around $650 billion this year, according to Bloomberg News. Investors were displeased. Amazon ended last week 13% lower than its Monday close. Both Meta and Alphabet lost around 6.3% each. Unsurprisingly, TSMC rallied on the news.

This reaction seems quite dichotomous. Tech companies are raking in profits and AI is surely a “thing,” yet investors are worried whether they can keep making money. But two things can be true at once.

“The sense in the marketplace is that even though your company is doing great and making a lot of money … if you’re overdoing it, we want to back away from your company,” economist Cary Leahey of Columbia University told BBC’s World Business Report last week. “That’s a big difference from the bubble in 2000 — in the internet and dot-com bubble — because those companies weren’t making money.”

Some people cling to the notion that companies who are raising capex, have the money to do so, and are investing in something that truly is world-changing ought to be insulated from market sell offs, or even bankruptcy. This sentiment in turn drives people to blame the likes of TSMC for not investing enough to make the infrastructure upon which this brave new world will be built.

Nobel Prize winner and MIT economist Daron Acemoglu summarized the challenge of connecting massive capex to higher revenue during that same BBC broadcast.

“The major problem is that while AI remains a very promising, very versatile technology, the huge amount of investment that we are seeing is not translating into revenue,“ he said. “And it’s not clear how it will translate into revenue because the types of applications that would make businesses adopt AI with large workforces are not there yet.”

There are quite a few differences between the current bubble and the dot-com era, some of which I outlined last December in “This AI Bubble is More Memory Than Dot-Com.”

The one I want to highlight, though, is that this time around AI expenditure is largely occurring either within the bosom of massive cash-rich public companies, like Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet, or inside black-box startups such as Anthropic and OpenAI who are funded by FOMO-driven VCs, or vendors eager to keep inflating the bubble. In each scenario, the losses can either be hidden or plugged such that the world needn’t see nor worry about them.

On the flipside, there are only a few companies who stand truly naked to the winds of the AI boom. TSMC is one, as are Nvidia and AMD. Only one of those three, however, has a huge annual capex bill.

For public-market investors, the protection afforded by the mothership is more robust than what they enjoyed 25 years ago while riding the dot-com bubble while at the same time trying to avoid its collapse.

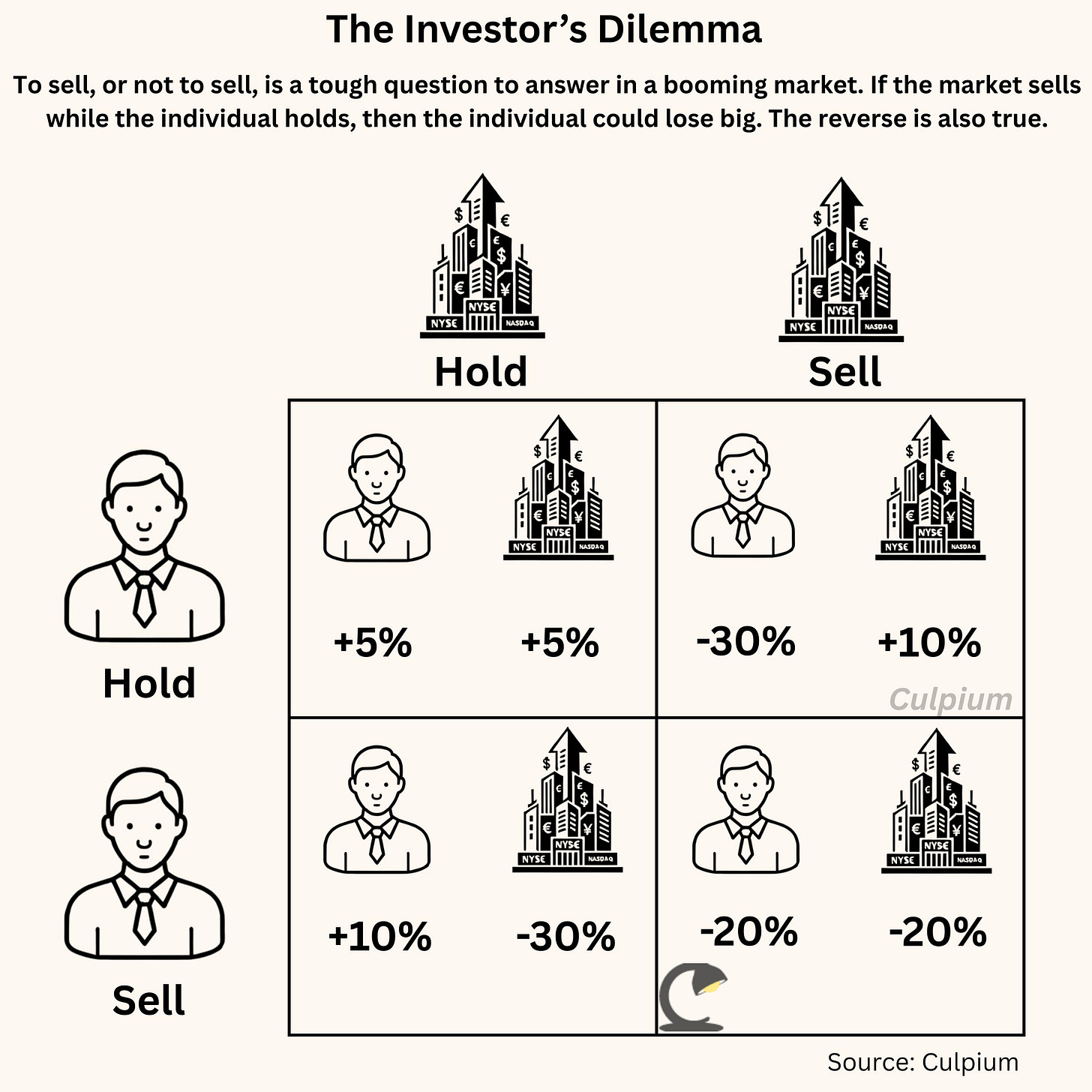

But now the granddaddy signal poses a new conundrum. Akin to the Prisoners’ Dilemma, we have the Investor’s Dilemma. In the Prisoners’ Dilemma, each suspect has the choice to confess or stay silent. Each choice determines the prison sentence, but you cannot know what your fellow inmate will do.

The 200-day MA is a well-known and closely tracked trend. If we pit retail investors against “the market,” then the problem is whether to sell now and take profit, or hold on in the hope of gaining more profit (and avoid losing out on further upside). The answer depends on what the other will do, but we cannot know their choice.

John Nash has an answer. The Nobel Laureate in economics was a game theorist who came up with a concept now known as the Nash Equilibrium. Applied to the Prisoners’ Dilemma it suggests that it would be most rational for any individual suspect to confess, even if that’s not the strictly optimal decision. Apply it to the Investor’s Dilemma, and we may have a possible solution. Let me point out, though, that I am neither an analyst or investment advisor. Make your own decisions.

If the 200-day MA really is the signal that investors are following, then some may feel it’s time to make a decision. If it’s not the data point they care about, or the Magnificent Seven isn’t the basket of stocks they track, then perhaps there’s other factors to consider.

The Investor’s Dilemma can also apply to companies spending on — or investing in — the equipment to build and run AI. If any individual company holds off, then maybe they’ll cap their returns but also limit possible losses. If they invest, they may make greater returns if no one else invests but lose a whole lot more if they all do.

What’s important to keep in mind, though, is that not every company invested in the future of AI has the same investment cost nor will get the same investment return. At least with the 200-day MA, there’s another data point to consider — and worry about.

I thought this was interesting, so I thought I’d share.

Thanks for reading.

I wonder what revenue those Hyperscalers expect to result from this enormous Capex, and how they arrived at those revenue numbers? My impression is that a lot of it is "keeping up with the Joneses", i.e. we plow tons of money into AI because our competitors do so. But, I might be wrong, so I'd really welcome input!

Also, a few months ago, I changed my mind about Apple's approach to AI. I used to think they're behind, but then concluded that they're actually the smart ones of the bunch: let others spend hundreds of billions of dollars on their efforts, and then contract with whoever has the best model to satisfy their (Apple's) customer demands. For Apple, that is, for now, Google and Gemini.